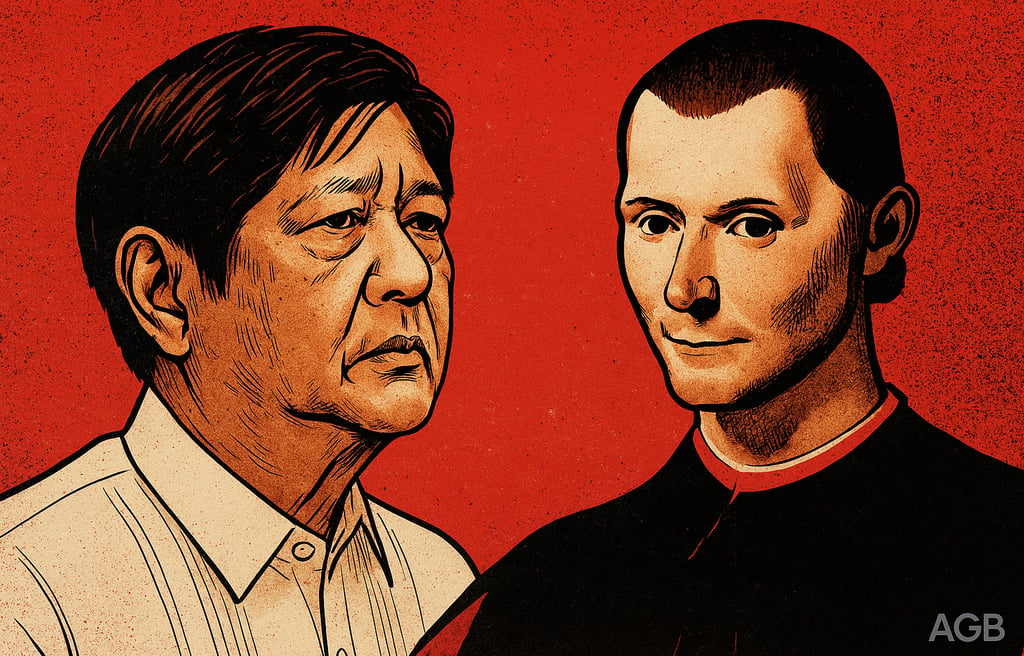

Bongbong Marcos Through the Lens of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince

This is how I see Bongbong Marcos—through the lens of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. It’s not a simplified take, and it’s not meant for everyone. Just a quiet reflection on power, control, and the kind of leadership we’ve learned to accept.

I first picked up The Prince at 17, inside the walls of a seminary. Strange place to meet Machiavelli, but that’s how it happened—while others wrestled with the idea of virtue, I found myself face-to-face with a man who didn’t pretend people were always good. That book didn’t make me cynical. It made things clearer.

And I didn’t just read it once. I kept going back to it. Because while the world keeps asking leaders to be saints, Machiavelli says no—they’re survivors first. That’s the version of power I understood even back then.

Maybe that’s why I’ve learned to stay still when it comes to politics. Ataraxia, they call it. Detached, but not indifferent. It’s a habit you pick up from silent halls and watching people long enough. So now, when I look at Bongbong Marcos Jr., I don’t just see a president. I see a case study. A live reading of Machiavelli in motion. And whether we like him or not, I think Machiavelli would’ve watched him, too—with interest.

The Prince Returns: A Calculated Resurrection

Machiavelli once said that half of what happens to us is luck—fortuna—but the other half is what we do with it.

In Bongbong Marcos Jr.’s case, it’s hard to ignore how that second half played out. His journey from exile to Malacañang wasn’t a comeback. It was a long, steady climb—quiet, strategic, and timed just right.

When the Marcos family fled in 1986, the exit was messy. But the return? That was slow, deliberate, and strangely methodical.

By 1992, barely a year back on Philippine soil, Bongbong had already secured a congressional seat in Ilocos Norte. He cycled through positions after that—governor, congressman again, senator. Then came 2016. He lost the vice presidency to Leni Robredo. It should’ve ended there. But he didn’t walk away.

Instead, he used the loss. Turned it into fuel. Repackaged himself. Took to social media, leaned into historical distortion, framed himself as the one wronged, not the one to blame. That shift didn’t happen overnight. It took years. But by 2022, he wasn’t just running. He was winning—and by a margin we hadn’t seen in decades: 31 million votes. People called it a landslide. But landslides don’t happen without groundwork. That victory was engineered.

They say history is written by the winners. In this case, the Marcoses came back holding the pen—and the printing press.

Unity as Strategy: The Formation and Fracturing of the UniTeam Alliance

If there was ever a textbook example of power over principle, it was the UniTeam. Marcos Jr. joining forces with Sara Duterte wasn’t about shared values. It was cold math. She had the southern vote, he had the north. Competing would’ve split the numbers. So they joined hands—not as partners, but as players who knew how to win.

Sara got the vice presidency. Bongbong took Malacañang. And on paper, they sold it as “unity”—a word that sounded nice, but meant almost nothing.

From the start, it was a transaction. Political analyst Don McLain Gill said it plainly: “I never, for one instance, believed that it’s going to be a long-term partnership. They merged because they just wanted to win.” That’s it. No illusions. And by 2024, the cracks were already showing. Conflicts over confidential funds, cabinet positions, and internal turf wars eventually led to Sara’s resignation from Marcos’s cabinet.

Then came Independence Day 2024. Reporters asked her if the UniTeam still existed. She didn’t dodge. “No, we are not candidates anymore,” she said.

Machiavelli would’ve nodded. He never expected alliances built on ambition to last. When the purpose is power—not loyalty—fractures aren’t a failure. They’re part of the script. And in this case, the ending was always coming. The UniTeam was never a marriage. It was a deal—with an expiration date.

Master of Balance: The South China Sea and Foreign Policy Realism

Foreign policy is usually where the masks slip. Campaign promises give way to real-world pressure, and you start to see how a leader thinks. In Bongbong Marcos Jr.’s case, this is where the Machiavellian shows up clearly.

During the 2022 campaign, he played it safe on China. Said we couldn’t afford to go to war, insisted diplomacy was the way forward. It was the usual soft approach—a message designed not to rattle Beijing or the business elite. But once he took office, the script changed.

He didn’t cut ties with China, but he leaned hard into the alliance with the U.S. Four new military bases were added under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, bringing the total to nine. By 2024, the Philippines and the U.S. were locked into over 500 military engagements—joint patrols, exercises, logistics. That's not drift—that’s a pivot.

Then came Ayungin Shoal. Chinese vessels harassed Philippine resupply missions. Marcos didn’t stay quiet. He filed protests. He spoke out publicly. And by May 2024, he was standing at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, calling out China’s behavior—without naming it, but with language sharp enough to cut through the usual diplomacy.

Still, he didn’t shut the door. His government kept talking to Beijing through the Bilateral Consultation Mechanism. In January 2024, both sides agreed to “calmly deal with incidents, if any, through diplomacy.” So on one hand, public defiance. On the other, private engagement.

This isn’t inconsistency. It’s strategy. Machiavelli wrote that a ruler should be a lion and a fox—strong enough to scare the wolves, sharp enough to see the traps. Marcos seems to be trying both.

Governing Through Control: The Role of Institutions and Funds

Machiavelli was clear on one thing: a ruler doesn’t just lead. He controls. And to do that, you need to tighten your grip on institutions—the courts, the budget, the rules of the game. Marcos Jr. knows this. But he didn’t have to build it from scratch. A lot of the scaffolding was already there, thanks to Duterte.

As of 2025, 13 out of 15 Supreme Court justices are Duterte appointees. That’s a bench already leaning in your favor. Then in June 2025, Marcos made his first move—appointing Court Administrator Raul Villanueva as Associate Justice. During the oath-taking, Marcos didn’t even pretend this was just ceremonial. He said it himself: the appointment would bring the branches of government “even closer than before.” That’s not subtle. That’s a signal.

Then there’s the confidential and intelligence funds—the CIFs. The Office of the President kept a ₱4.5 billion allocation for both 2024 and 2025. It’s split between ₱2.25 billion in confidential funds and ₱2.31 billion in intel funds. But here’s the kicker: by the end of 2024, only about 25.8% had been used. Just ₱1.16 billion spent out of ₱4.5 billion.

To most people, that might look like underspending. But through a Machiavellian lens, that’s not the point. These funds don’t need to be used to be useful. Their mere existence signals power. They give flexibility, they create silence, and they remind everyone who holds the strings.

Governance as Political Performance

Machiavelli understood something most people forget: what you look like often matters more than what you actually do. Image isn’t a bonus—it’s part of the job. And Marcos Jr. seems to have taken that to heart. Unlike Duterte’s off-the-cuff firestorms, Marcos leans into scripting. His team calls it “deliberate” and “systematic.” It’s not chaos. It’s choreography.

Take the POGO ban. During his State of the Nation Address in July 2024, he declared: “Effective today, all POGOs are banned.” Lawmakers broke into applause. Chants of “BBM! BBM!” filled the room. It looked like a bold move. But look closer—it wasn’t spontaneous. It was staged. Timed perfectly to ride the wave of public frustration over POGO-linked crimes. It wasn’t just policy. It was theater.

Same playbook with the Maharlika Investment Fund. In October 2023, with pressure building and criticism mounting, Marcos Jr. announced a pause. He said he needed to “study carefully the IRR” to make sure it delivered development while staying “transparent and accountable.” That move didn’t kill the fund. It bought him time. Time to reframe, tweak, regroup. Classic crisis management: acknowledge the noise, don’t admit failure, and keep the long game intact.

This isn’t governance in the fix-the-system sense. It’s about reading the mood, adjusting the volume, and keeping control of the room. When pressure builds, you don’t crack—you pivot, stall, or reframe. It’s not about solving everything. It’s about staying in front of the cameras looking like you’re in charge, even when the mess is still there. That’s not incompetence. That’s the performance.

The Structural Reality: Political Dynasties and Elite Capture

If you want to understand Marcos Jr.’s rise, you can’t stop at personality. You have to zoom out and look at the structure holding everything up. Because underneath the speeches and strategy, there’s a machine—and it’s run by families.

According to the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, political dynasties dominate every level of government. As of the 2024–2025 data:

71 out of 82 provincial governors come from dynastic families.

80% of district representatives in Congress are from political clans.

113 of 149 city mayors belong to the same system.

And nearly 250 political families control power across all 82 provinces.

The trend isn’t slowing down. In 2004, dynasties made up 48% of Congress. Now it’s 67%. Mayors from political clans went from 40% to 53%. And among these clans, 18 are labeled “obese” dynasties—with five or more family members running in different positions at the same time. The Marcoses are on that list.

Even more alarming, 4.5% of all contested positions—about 800 seats—had only one candidate: someone from a political clan. Nobody dared run against them. That says a lot about how deep the grip of these families goes.

So yes, Marcos Jr. made strategic moves. But much of what looks like political brilliance sits on top of old, reinforced structures. When your family name already opens doors, clears opponents out of the way, and holds multiple seats at once, strategy becomes less about navigating challenges and more about managing what's already yours to lose.

The Machiavellian Paradox: Unity Through Fragmentation

Marcos Jr. ran on the promise of unity, but what he's actually doing is the opposite. And it’s working.

While UniTeam was paraded as this grand coalition, its real use was to win the election. After that, it started falling apart—and he didn’t rush to fix it. If anything, he let it happen. Kept his base close. Let ideological rivals wear themselves out. Co-opted the moderates. No big confrontations, just quiet maneuvering that keeps everything moving around him.

His growing distance from Sara Duterte might look risky on the surface. But stepping away from the weight of the Duterte brand might give him more room to shape the field before 2028. There’s no need to share the spotlight—or the power—when the alliance has served its purpose.

Some analysts think he’s prepping the ground for a Marcos-aligned successor. Maybe. Maybe not. What’s clear is that he’s willing to trade temporary tension for long-term freedom of movement. You don’t need public harmony when you’ve already figured out how to manage the noise.

Institutional Victories: The Silent Accumulation of Legal Wins

Since Marcos Jr. stepped into office, one thing has moved quietly but consistently: the legal clearing of his family’s name.

Seven cases tied to the Marcos family’s ill-gotten wealth have now been dismissed. That amounts to roughly ₱2.3 billion in assets they no longer have to answer for. No big press conferences. No legal triumph speeches. Just quiet wins stacking up while attention is focused elsewhere.

The most recent case, worth ₱276 million, was thrown out in October 2024. The reason? “Excessive delays.” It had been sitting in court since 1987. That’s 37 years. The court said the case dragged on so long that it was no longer fair to the accused—witnesses likely gone, documents probably missing. Not a ruling on guilt or innocence—just a procedural dead end.

This is the pattern. Dismissals based on delay, missing evidence, or flawed process—not because the claims lacked merit, but because time did what no lawyer could. When the system moves slow enough, you don’t need to win in court. You just need to wait.

And that’s the kind of patience Machiavelli would’ve respected.

The Global Context: Learning from Machiavellian Masters

Marcos Jr. didn’t invent this style of leadership. He’s just the latest to wear it well.

We’ve seen this before—in different countries, under different names. Leaders who consolidate control, silence opposition, bend institutions in their favor, and build power not through ideals, but through timing, strategy, and leverage.

Vladimir Putin built his rule through palace intrigue, fear, and a state media machine that controls the national mood. Xi Jinping rose by eliminating rivals under the banner of anti-corruption, then rewrote the rules to stay in office indefinitely. Erdoğan has turned crisis into a ladder, polarizing the public while tightening his grip. Even Trump, in his own chaotic way, used confusion as a weapon—keeping allies dependent, enemies off-balance, and the spotlight always centered on him.

Then there are the quieter tacticians. Tony Blair reframed a whole political party while managing internal factions like a CEO. Angela Merkel ruled with silence and timing, often removing threats without ever raising her voice. Macron adapts constantly, pulling from left and right depending on where the wind blows. Lee Kuan Yew—the most openly Machiavellian of them all—said it plainly: fear gets more done than love.

But it’s worth saying this out loud: effectiveness doesn’t make something admirable. A lot of these leaders left behind strong states—but also broken institutions, silenced dissent, or worse. Some used these methods to steer their countries forward. Others used them to justify repression, corruption, even war. That’s the danger of Machiavellian statecraft—it works. And when it works too well, it becomes hard to stop.

This isn’t a praise list. It’s a pattern. And the fact that Marcos Jr. fits the shape—even loosely—shouldn’t flatter anyone. He may not rule with the same force, but the instincts are there. Strategic alliances, image control, institutional consolidation, long-term positioning. In countries like ours, where people are tired of disorder and just want things to move, this kind of leadership doesn’t just survive—it flourishes.

And that’s exactly why it needs to be watched.

Limits of the Machiavellian Lens: Are We Giving Him Too Much Credit?

Here’s the thing about spending years with The Prince: eventually, you start seeing strategy everywhere—even when it might not be there. And that’s the risk. Not everything that looks deliberate is actually planned.

The numbers tell a different story. When 87% of governors, 80% of Congress, and 113 city mayors come from political dynasties—when 800 local races go uncontested because no one dares challenge the family name—it’s hard to argue that any one person is outplaying the system. In a setup like that, survival isn't genius. It’s inheritance.

The 1987 Constitution says political dynasties should be banned. But in the decades since, they’ve only grown stronger. Research shows why: entrenched families know how to adapt. They build networks, hoard resources, mobilize loyalty, and wear the system like armor. Marcos Jr. doesn’t have to fight for control in that world—he’s been raised in it.

Even the legal victories his family has stacked up—those case dismissals on procedural delays—might not be the result of masterful defense. Maybe the cases just sat too long. Maybe the evidence disappeared, or the witnesses died, or the prosecutors gave up. When institutions decay, you don’t need to win. You just need to wait.

And this is where the Machiavellian lens can mislead. It tempts us to find strategy where there might only be luck, or timing, or rot. Academic studies even warn against this kind of over-reading—what they call pattern-seeking bias and cherry-picking. You zoom in so hard on the supposed brilliance, you forget to ask: could this all just be baked into the system?

If we’re being honest, Machiavelli might agree. Not every outcome is the work of a cunning prince. Sometimes, it’s just the system doing exactly what it was rigged to do.

Comparative Perspective: Authoritarianism in the Modern Philippines

If we want to understand why this kind of leadership lands well in the Philippines, we have to look beyond the man. The conditions were already there.

Research on political culture shows a strong tolerance—sometimes even a preference—for what scholars call “political illiberalism.” That means people still say they support democracy, the rule of law, and institutions—but they also want a strong leader who can get things done, even if it means cutting corners. There’s a built-in contradiction, and it’s been there for years.

Under Duterte, this gap got wider. His administration made it normal to sideline checks and balances, to discredit media, to treat dissent as criminal. Institutions didn’t collapse—they just got softer. More flexible. Easier to shape. That created the perfect handoff: Marcos Jr. didn’t need to reinvent authoritarian tools. He just had to inherit and repurpose them.

Add to that the disinformation networks, the myth-building, the slow erasure of political memory—and it’s not hard to see how the stage was set. Marcos Jr. didn’t have to scheme his way through a hostile environment. He stepped into a setup where the hard work of dismantling accountability had already been done for him.

In a place where the public’s learned to expect strongmen, this kind of leadership doesn’t feel like a break from the past. It feels like a continuation.

Democratic Implications: The Price of Effective Statecraft

If you judge leadership by control, Marcos Jr. is doing fine. He’s built alliances, kept institutions on his side, and kept rivals in check. But when you start looking at how this affects ordinary people, or what it’s doing to democracy itself, things start to look different.

Studies on political dynasties in the Philippines don’t just talk about power. They connect it to poverty. To corruption. To nepotism. They show how these families use their positions to protect themselves, bend rules in their favor, and make sure they stay in power. And because people have seen the same names for so long, they stop expecting anything different.

Right now, nearly 250 families hold political control across all 82 provinces. In some areas, nobody even bothers running against them anymore. That’s not just dominance—that’s a public that’s grown tired, maybe even hopeless.

It gets worse. Research shows that the more these families tighten their grip, the more likely it is that violence follows. Governance becomes less about service, more about keeping power inside the circle. And when people feel completely shut out—when they see that elections won’t change anything—some eventually look for other ways to fight back.

So yes, Marcos Jr. may look like an efficient leader. But what we’re also seeing is the slow breakdown of accountability, the silencing of challengers, and a system that keeps rewarding the very people who’ve made it harder for real democracy to take root.

Conclusion: The Modern Prince and a Constructed Republic

Marcos Jr.’s presidency is many things, but above all, it’s a case study. A live example of how Machiavellian thinking still works in today’s political systems—especially in places where the conditions make it easy.

His return to power wasn’t accidental. It was years in the making. Strategic alliances, carefully shaped public messaging, foreign policy pivots, legal wins, and a slow, steady grip on institutions—it all adds up. On paper, it would make Machiavelli proud.

But that only tells half the story.

Because the truth is, you don’t need to be a political mastermind when the field is already rigged to your advantage. The same presidency that looks efficient and calculated is propped up by a system that protects the powerful. A system that lets ₱4.5 billion in confidential funds sit untouched but always ready. A system where 87% of governors belong to political families. A system where seven cases of ill-gotten wealth can disappear—not because the accused were cleared, but because the cases were too old, too slow, or too quietly buried.

If Marcos Jr. is Machiavellian, then so is the republic that made his return possible. Here, power doesn’t die—it just changes hands within the same circles. The names on the ballot change a little. The playbook doesn’t.

We keep hearing the word “unity,” but what we see is division being managed, not resolved. We call it democracy, but half the races are uncontested. There’s no real contest when the outcome is already understood.

And as someone who’s gone back to The Prince more times than I can count since those quiet seminary nights, I don’t say any of this to sound jaded. I say it because clarity matters more than comfort.

If this is what political success looks like, we have to stop staring at the strategy and start asking harder questions. Why do we keep voting for names that already hold the keys? Why have we allowed a system that rewards control over service, silence over accountability? Why do we mistake survival for brilliance?

Marcos Jr. may be a modern prince. But the deeper question is about us. What kind of country keeps making space for this kind of leadership—and what will it take to break the cycle?

The prince isn’t the problem. It’s the people who keep rebuilding his throne.

SOURCES:

Putin and Machiavelli

https://bobbymcgonigle.github.io/Putin-and-Machiavelli.htmlThe Influence of Machiavellian Ideas on Contemporary Politics: Putin as a Case Study

https://nicklasnickel.com/2023/04/19/the-influence-of-machiavellian-ideas-on-contemporary-politics-putin-as-a-case-study/Putin and Political Theory

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=134935Xi’s Personnel Mismanagement

https://jamestown.org/program/xis-personnel-mismanagement/Putin’s Playbook

https://ucigcc.org/blog/putins-playbook/Putin’s Machiavellian Repression

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/putins-machiavellian-repression-backfiring-ukraine-204672Putin and Political Theory: A Machiavellian and Pan-Slav Mindset

https://www.europenowjournal.org/2022/02/24/putin-and-political-theory-a-machiavellian-and-pan-slav-mindset/Xi Jinping: What Would Machiavelli Say?

https://nationalinterest.org/feature/xi-jinping-now-chinas-president-life-what-would-machiavelli-24742Has Xi Jinping Made China’s Political System More Resilient?

https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/has-xi-jinping-made-chinas-political-system-more-resilient-and-enXi Jinping 2.0

https://bitterwinter.org/xi-jinping-2-0-a-cold-brutal-power-machine/Conservatism and Authoritarianism in Turkey

https://silkroadstudies.org/publications/joint-center-publications/item/13224-erdogan%E2%80%99s-journey-%E2%80%93-conservatism-and-authoritarianism-in-turkey.htmlErdoğan’s Machiavellian Pragmatism

https://www.mena-researchcenter.org/recep-tayyip-erdogans-macchiavellian-pragmatism-a-strategic-dance-on-the-global-stage/Turkey’s Authoritarian Turn

https://www.theweek.in/news/middle-east/2025/05/16/turkey-s-authoritarian-turn-erdogan-s-regime-is-shedding-its-democratic-pretence.htmlErdoğan’s Populist Formula

https://www.populismstudies.org/erdogans-winning-authoritarian-populist-formula-and-turkeys-future/Machiavelli’s Tiger: Lee Kuan Yew and Singapore’s Authoritarian Regime

https://www.academia.edu/964086/Machiavellis_Tiger_Lee_Kuan_Yew_and_Singapores_Authoritarian_RegimeLee Kuan Yew Obituary (BBC)

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32046144Lee Kuan Yew: The Man and His Dream

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/lee-kuan-yew-the-man-and-his-dream/Machiavelli’s Tiger – Readkong

https://www.readkong.com/page/machiavelli-s-tiger-lee-kuan-yew-and-singapore-s-7146827Strategic Mastery – LinkedIn

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/strategic-mastery-lee-kuan-yew-deep-mind-behind-suresh-surenthiran-2i33fFranklin D. Roosevelt as Statesman

https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/fdr-as-statesman/Roosevelt’s Political Model

https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/downloads/js956k90g?locale=enChurchill: Prophet, Pragmatist, Idealist

https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/speeches-about-winston-churchill/prophet-pragmatist-idealist-and-enthusiast/Churchill and Alliance Politics

https://warontherocks.com/2018/01/shall-fight-tabletop-game-churchill-teaches-us-alliance-politics/Machiavellian Leaders in Modern Times

https://indiafellow.org/blog/all-posts/machiavellian-leaders-in-modern-times/Machiavellianism in Leadership

https://www.eighthmile.com.au/blog/machiavellianism-in-leadershipMachiavelli and Philippine Politics

https://www.newmandala.org/machiavellis-eyes-leaders-citizens-philippine-politics/Political Families in the Philippines

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_families_in_the_PhilippinesPCIJ Political Dynasties Report

https://pcij.org/2024/12/08/governors-political-dynasties-philippines-provinces-elections/Marcos Ill-Gotten Wealth Case Dismissals

https://philippinerevolution.nu/2024/10/21/groups-condemn-dismissal-of-7th-case-against-marcos-ill-gotten-wealth/Sandiganbayan Dismisses P276M Marcos Case

https://pia.gov.ph/sandiganbanyan-dismisses-p276-m-ill-gotten-wealth-case-vs-marcos/Anti-Graft Court Dismisses Marcos Case (BenarNews)

https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/philippine/philippines-anti-graft-court-dismisses-5m-ill-gotten-wealth-case-against-the-marcoses-10092024144834.htmlSC Affirms Dismissal of P105B Marcos Case

https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/07/19/2282254/sc-affirms-dismissal-p105-billion-marcos-ill-gotten-wealth-case

Contact us

subscribe to morning coffee thoughts today!

inquiry@morningcoffeethoughts.org

© 2024. All rights reserved.

If Morning Coffee Thoughts adds value to your day, you can support it with a monthly subscription.

You can also send your donation via Gcash: 0969 314 4839.