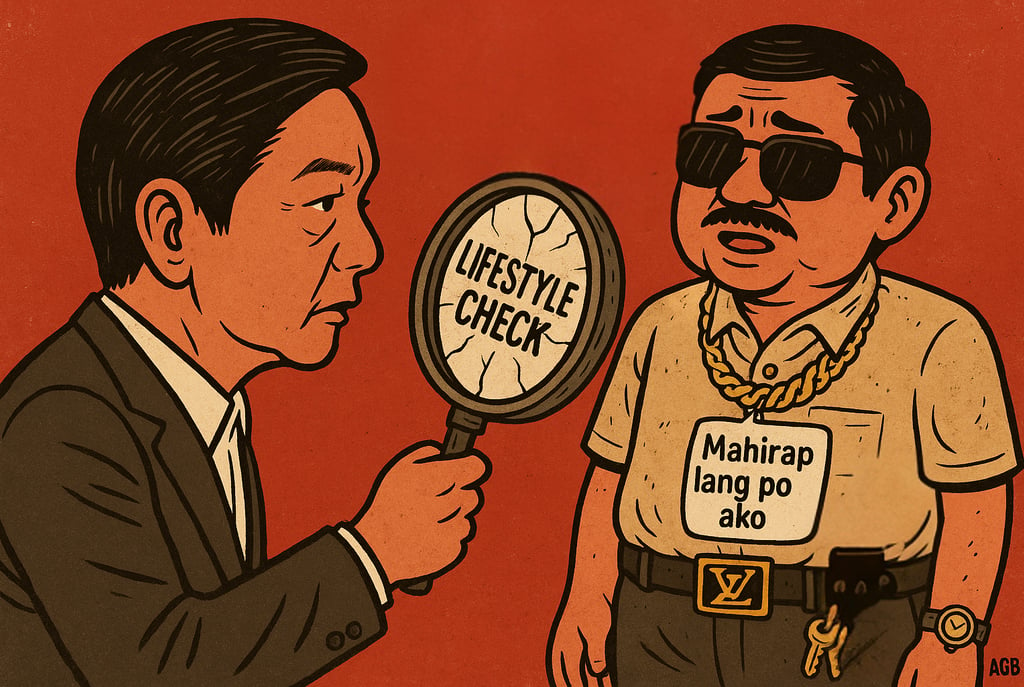

[COMMENTARY] Lifestyle Checks in the Philippines: Why the System Keeps Falling Apart

We all want a system that calls out officials living beyond their means. The lifestyle check was supposed to do that. But with loopholes, politics, and a weak framework, it’s become more ritual than reform. Still, we hold on to it — because when it works, it shows us the kind of accountability we desperately need.

This draft goes back a few months. I did the research out of curiosity, filed it away, and forgot about it. At that time, Morning Coffee Thoughts was just a website that nobody paid attention to, not the Facebook page it is today.

Someone asked me about this topic earlier today, and that reminded me of what I had written. Good thing the draft was still here. It only needed an update, especially with Malacañang now pushing to revive lifestyle checks. That gave me reason to return to it, dust it off, and see what the system really looks like today.

I’ve always wondered how a public servant enters office with modest means and, in just a few years, ends up with mansions, SUVs, and businesses tucked under their spouse’s or children’s names. The law says we have a tool to check that kind of excess — the lifestyle check. But after looking at how it works, it feels less like accountability and more like a stage play.

The Framework and Process of Lifestyle Checks

Legal Foundation and Constitutional Basis

The backbone of lifestyle checks is the SALN — Statement of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth. The 1987 Constitution says it clearly: “public office is a public trust,” and officials must “lead modest lives.”

Republic Act 1379 (1955) allows forfeiture of illegally acquired property. Republic Act 6713 (the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards) requires annual SALNs. And Republic Act 3019 (the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act) is supposed to give the whole thing teeth. The operative word? "Supposed to."

Every official has to file a SALN within 30 days of taking office, then yearly by April 30. It must list everything: houses, cars, land, stocks, debts, businesses, and even the properties of a spouse or minor children. In theory, one undeclared property should be enough to trigger a red flag.

Implementation Process and Methodology

The steps look neat when written down:

Identify targets

Gather data

Confirm and validate

Build a case

Open preliminary investigation

File in court

Investigators compare declared income with actual lifestyle — a net-worth check, a bit of surveillance, a lifestyle questionnaire here and there. The DOF’s Revenue Integrity Protection Service (RIPS) has been active, zeroing in on Customs, BIR, and DPWH. SALNs are checked against land titles, vehicle registrations, and other government databases.

On paper, it seems solid. In reality, it feels like a race with one leg tied.

Why It Keeps Falling Apart

Severe Resource Constraints

At one point, the Ombudsman had 37 investigators for 1.5 million government officials. That’s one investigator for 17,241 people. Even when the number went up to 93, it was still hopeless.

Hong Kong’s ICAC has ₱4.94 billion and 1,326 staff for 174,175 officials. The Philippine Ombudsman? ₱480 million, 1,141 staff, and a mandate to cover 1.5 million people. Prosecutors here earn around ₱500,000 a year — about the same as fresh law graduates in Makati.

Half a million pesos sounds decent, until you realize it’s peanuts when you’re up against systemic corruption. We expect miracles with pocket change. 🤷

When Time Becomes the Escape Plan

RA 3019 gives corruption cases a 15-year life span. SALN violations expire even earlier, depending on the offense. That means plenty of cases get tossed simply because they were filed too late.

The Supreme Court has tried to set rules, saying prescription starts at filing since SALNs are mandatory. But rulings vary. Investigations move at snail’s pace. By the time cases finally reach court, the clock has already run out.

In the Philippines, you don’t even need a brilliant defense. Just wait it out. Time itself becomes the judge, and its verdict is freedom.

Politics Breaks It

Then came Samuel Martires. In 2020, as Ombudsman, he halted lifestyle checks altogether. He argued RA 6713 was “vague” and that wealth didn’t necessarily mean corruption. Public access to SALNs was cut. You now needed the official’s permission to view their own declaration.

Martires even floated the idea of jailing anyone who comments on SALNs. Imagine that — a tool meant to keep officials honest turned into something locked away, with penalties for talking about it. Add the endless reshuffling of anti-graft bodies between Malacañang offices, and the system didn’t just weaken. It crumbled.

At first, I thought "Martires broke the system." But how can one man break an already broken system.

That was the moment I stopped believing lifestyle checks meant anything.

How the System Trips on Its Own Rules

Even when lifestyle checks happen, the process stumbles over itself. Section 10 of RA 6713 requires officials to be notified of SALN errors and given a chance to fix them before charges stick. Too often, that step gets skipped. And cases collapse.

SALNs are kept for only ten years before they’re shredded. So if someone built their wealth in the ’90s, the trail is gone. No documents, no case. Like corruption here comes with its own expiration date.

Success Stories and Convictions

It hasn’t all been failure. Some cases landed.

Jed Patrick Mabilog, Iloilo City Mayor, was dismissed in 2017 after his wealth jumped by ₱8.9M in just a year. The Court of Appeals upheld it. In 2025, Marcos gave him executive clemency, but the case still stands as one of the few real wins.

Between January and August 2018, DOF-RIPS dismissed five Customs officers for false SALNs. Among them were spouses Uthman and Rosalinda Mamadra, who hid properties in Parañaque, Cavite, and Mindoro, plus 12 firearms and several vehicles.

Delia Morala of the BIR was convicted of falsification for not declaring her husband’s businesses.

Ester Grafil Sese, a Customs aide earning ₱78,000 a year, somehow owned vehicles, firearms, and properties. She was dismissed.

Visitacion Difuntorum, a Customs officer, was fined for undeclared properties in Quezon City and Samar.

By 2006, the Ombudsman had flagged ₱1.2B worth of suspected ill-gotten assets. The PAGC ran 175 lifestyle checks: three failed, 46 dragged on, the rest got forwarded to other agencies. Each case cost around ₱100,000 and took almost a year to move.

The system works, but only in flashes. Most of the time, it sputters and stalls.

Dismissed Cases and Failures

Prescription Wipes Out Cases

Benjamin “Kokoy” Romualdez was charged for acts committed from 1976 to 1986. The charges came in 2001. Too late. Case dismissed.

In DOF-RIPS vs. Ombudsman, some charges moved forward, but others died because of prescription. That’s how technicalities save people who shouldn’t be saved.

When the Powerful Walk Away

The most political case? Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno. Instead of impeachment, she was ousted via quo warranto for failing to file certain SALNs as a UP professor from 1985 to 2006. The Court said she lacked integrity. Critics called it political weaponization.

Other officials walked free by showing their assets came from businesses, investments, or family contributions. The burden of proof falls on the state. And in a country where paper trails can be manufactured, that’s an easy hurdle to clear.

Due Process Violations

Courts have been clear: no chance to fix a SALN, no liability.

The case of Jessie Carlos nailed that point. The government failed to notify him about SALN deficiencies. The SC sided with him. Case dismissed.

Recommendations

Expand capacity: Add investigators by the thousands. Raise their pay.

Specialized units: Put RIPS-style watchdogs in every department.

Fix prescription rules: Standardize at 20 years. Apply discovery rule consistently.

Digitize SALNs: Mandatory e-filing with built-in validation.

Link databases: Land titles, vehicles, business permits, bank accounts, tax records.

Target high-risk officials: Use data analytics to spot anomalies.

Restore transparency: Reopen SALNs to the public. Reverse Martires-era secrecy.

Protect media and civil society: Stop the nonsense of criminalizing commentary.

Unify oversight: One anti-corruption body insulated from politics.

Special courts: Judges trained in graft cases to speed things up.

The Path Forward

The World Bank says the Philippines lost $40.6B to corruption from 1980 to 2000. That’s the cost of a system that doesn’t work. And we’re still bleeding money the same way.

Lifestyle checks could be powerful. They could scare officials into living honestly. But only if the government wants them to. Right now, they feel more like ritual than reform.

I’ve been watching this cycle for years. The names change, the loopholes don’t. Maybe one day lifestyle checks will finally bite. Until then, they remain what they’ve always been: promises on paper, and a system Filipinos know better than to rely on.

Contact us

subscribe to morning coffee thoughts today!

inquiry@morningcoffeethoughts.org

© 2024. All rights reserved.

If Morning Coffee Thoughts adds value to your day, you can support it with a monthly subscription.

You can also send your donation via Gcash: 0969 314 4839.