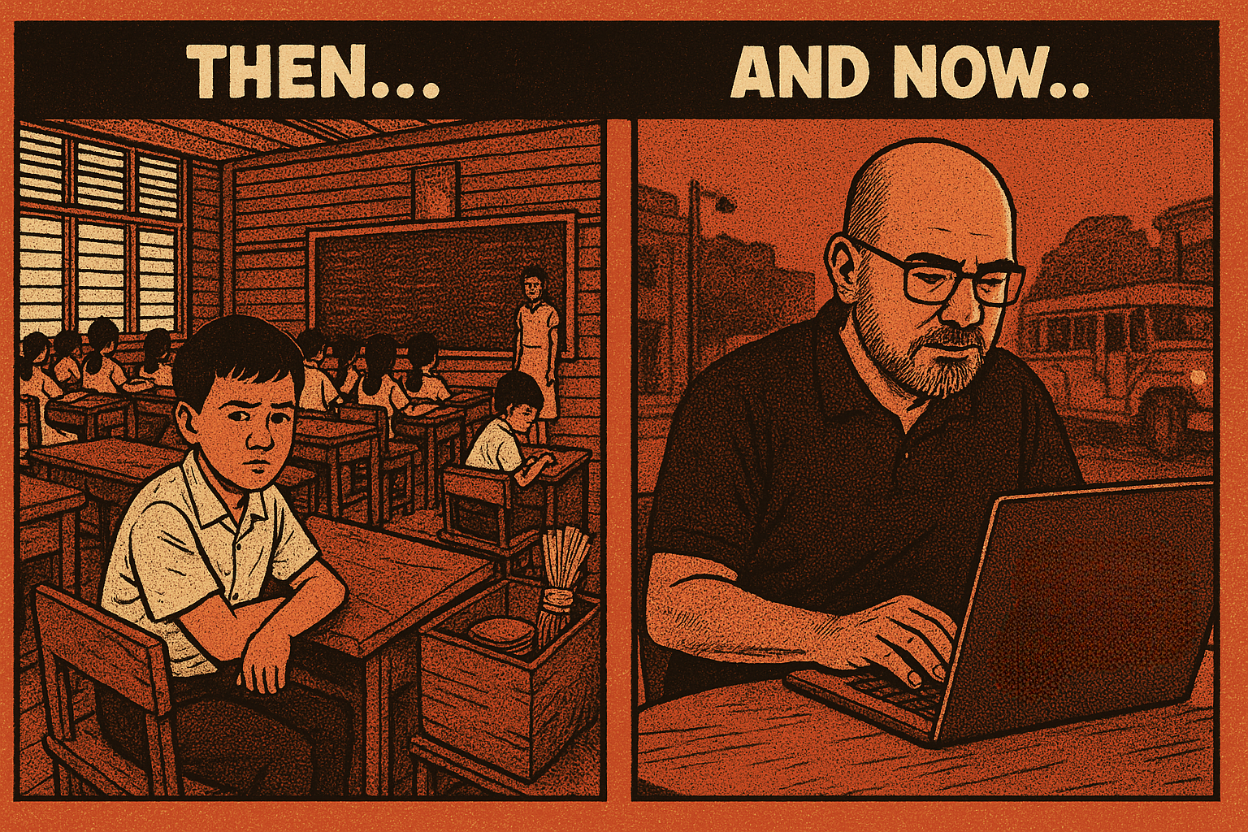

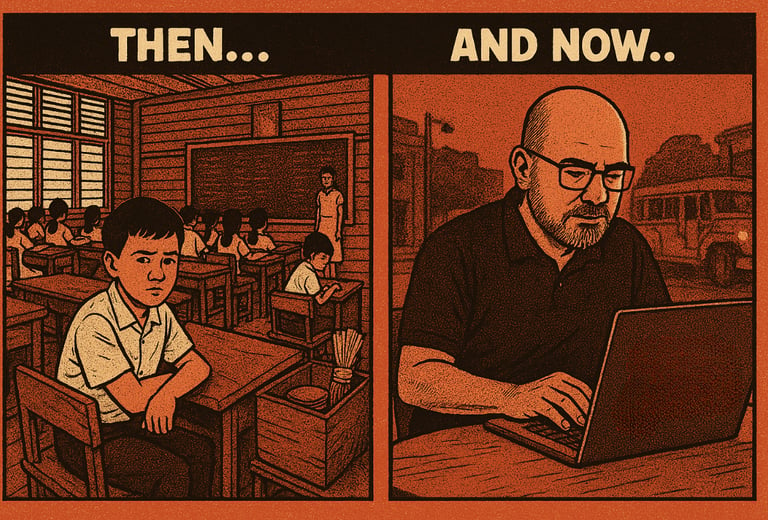

From Row Four to Critical Thinking: A Journey of Questions

A personal journey from the back row of a 1980s Philippine classroom to a writer’s desk decades later. This piece reflects on how curiosity, reading, and a priest’s simple lesson on questioning shaped the way I think, write, and practice critical thinking today.

Row four. Beside the wooden box filled with walis tambo, bunot, floor wax, and all the cleaning tools no student wanted to touch. If you grew up in the Philippines in the ’80s, you know what that spot meant.

That seat carried a quiet message about where the school thought you belonged.

That was my place. Second-to-the-last section. Fourth row.

I wasn’t the student teachers singled out for praise. While others absorbed lessons with ease, I was busy trying to keep up in a system built for quick answers and memorization.

Then came an unexpected turn. Fr. George Decasa, SVD, and a group of students from Christ the King Seminary visited our high school. It seemed like any other day, until they started calling names.

Mine was on the list. Row four. Me. I didn’t know what to make of it. Maybe they saw something I hadn’t recognized in myself yet.

The Unexpected Invitation

When Fr. Decasa announced that certain students had been selected for the seminary, I couldn’t believe my name was called. Me? The kid from row four? The one who couldn’t even get decent grades in regular subjects? Looking back, maybe they saw a kind of potential I hadn’t noticed in myself yet.

My stay at the seminary was brief. In a class of 27 seminarians, I was the weakest link academically. Philosophy, theology, Latin. These felt like foreign languages everyone else seemed to understand. I couldn’t catch up, and I eventually made the hard decision to leave. Those months still gave me something grades never could: exposure to a different way of thinking.

The Secret Weapon: A Voracious Appetite for Reading

Long before I ever heard the term “critical thinking,” I was already training my mind without knowing it. I grew up surrounded by books, magazines, and newspapers, thanks to my adoptive mother. History and politics fascinated me. Our house was lined with Reader’s Digest collections from the ’70s and ’80s, stacks of Newsweek and National Geographic, and shelves of books that pulled me in completely.

I read Primitivo Mijares’ The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos (1976) and the circulated pamphlet version of Ricardo Manapat’s Some Are Smarter Than Others in the late ’80s, before the expanded book was published in 1991. Teodoro Agoncillo’s History of the Filipino People (1960) was a constant presence, the same book countless students relied on through the ’80s and ’90s.

I spent afternoons with Lualhati Bautista’s Dekada ’70 (1983) and pored over Dictatorship and Revolution: Roots of People’s Power (1988), which gave context to the events I saw unfolding around me. Later, as the early ’90s came in, I picked up David Timberman’s A Changeless Land (1991), which helped me make sense of the post-EDSA political landscape.

These weren’t just books on a shelf. They were my escape, my teachers, and my training ground. While others memorized lessons by rote, I was piecing together stories from Mijares, Manapat, Agoncillo, Bautista, the Constantinos, and other critical voices of the era. History didn’t feel like something that happened long ago. It was alive, messy, and full of unanswered questions.

That habit of reading trained me to spot patterns others might overlook, to question inconsistencies, and to keep digging for what lay beneath the surface. It also shaped my ethical lens. Reading across different perspectives—whether through historical exposés, political analyses, or novels rooted in real struggles—taught me to ground my conclusions on fairness, honesty, and integrity. Without that anchor, critical thinking is just cleverness without direction.

The Breakfast That Changed Everything

During my time at the seminary, we would serve mass at different schools such as St. Paul College QC, Holy Spirit, St. Mary’s, and sometimes Xavier School. Those mornings were meaningful. Serving at the altar gave me a quiet sense of responsibility I hadn’t felt in a classroom.

But there was another part I looked forward to just as much: the breakfast that followed. The food was always excellent, and those shared meals became a space where real conversations happened.

One of my favorite priests to accompany was Fr. Rudolf Horst, SVD. He was gentle, thoughtful, and had a way of making you feel heard. One morning over breakfast, he asked how I was doing. Instead of giving the usual polite answer, I told him about my struggles, especially with philosophy.

He said many things that day, but one line has stayed with me ever since: “Critical thinking, in the simplest form, is all about asking questions and not taking things at face value.”

There were no complicated theories or fancy words. Just a simple truth that quietly reshaped how I approached everything that came after.

The Tools That Stuck

Fr. Horst didn’t stop at philosophy. He introduced me to practical tools I could actually use. The first was the Fishbone Diagram, also called the Ishikawa Diagram after its creator, Kaoru Ishikawa. He explained it simply: imagine a fish. The problem sits at the head, and every possible cause branches out like bones along the spine.

“Don’t just accept that something is broken,” he told me. “Ask why it’s broken. Then ask why that happened. Keep asking until you can’t ask anymore.”

He also taught me the Five Whys technique. His advice was clear: keep questioning until you reach the point where the answers stop revealing anything new. That habit of digging deeper stayed with me long after I left the seminary. The Fishbone and Five Whys gave structure to my curiosity and turned vague thoughts into something I could work with.

From Academic Struggle to Real-World Strength

Years later, I realized something about the way schools are built. The system tends to reward students who can recall information fast and follow patterns without missing a beat. That wasn’t me. I was never the one with the perfect recitation or the flawless memory.

What I did have was the habit of asking better questions. While my classmates memorized Aristotle’s ideas, I found myself wondering why he thought that way and whether his reasoning made sense in our time. That shift changed everything.

When I started writing about Philippine politics for Morning Coffee Thoughts, this mindset became my sharpest tool. In a landscape filled with spin, propaganda, and surface-level commentary, questions cut through the noise. Instead of stopping at what politicians said, I started asking why they said it, who stood to gain, what they were leaving out, and what would happen if their logic played out. That’s where real insight lives—not in the memorized lines, but in the questions that follow.

Critical Thinking in Everyday Life

Fr. Horst’s lesson stuck because it wasn’t meant for classrooms alone. Critical thinking applies to daily choices—who to vote for, which news to believe, what opportunities to take, and which claims deserve a closer look.

The first habit is to start with curiosity. Instead of jumping to conclusions, pause and ask what you don’t know yet. What assumptions are shaping the way you see things?

Next, question the source. Who’s giving you this information? What do they get if you believe it? Are there other angles you should consider?

Look for patterns. See if a claim fits with what you already know to be true. When something contradicts established facts, look for solid evidence before accepting it.

And always follow the money and power. In politics especially, asking “Who benefits?” often reveals motives hiding in plain sight.

These habits don’t require academic training. They only need curiosity, patience, and the willingness to keep asking questions when others have already stopped.

Building Your Critical Thinking Muscle

Like any skill, critical thinking gets sharper with practice. Small, consistent habits make a difference over time.

Start with better questions. Instead of the usual “How was your day?” try asking, “What was the most interesting thing that happened today?” or “What challenged you the most?” Questions like these push conversations beyond the surface.

Use the Five Whys outside the classroom. When something goes wrong—slow internet, heavy traffic, a work problem—don’t stop at the first explanation. Keep asking why until you reach the real cause.

Read beyond your usual sources. Don’t stay in the comfort zone of ideas that only confirm what you already believe. Seek out perspectives that challenge you.

Write your questions down. You don’t have to answer them right away. The act of listing them keeps your mind active and engaged.

Finally, examine your own assumptions. This is the hardest part. Ask yourself what you might be getting wrong and what kind of evidence would make you rethink your position.

These small habits, practiced regularly, keep your thinking sharp and grounded in reality.

The Difference Between Smart and Wise

Schools often equate intelligence with quick answers. The faster you respond, the smarter you appear. But wisdom grows in a different space. It shows up in the questions people are willing to ask, even when those questions slow everything down.

The student who asks why a formula works might not get praised for it, but that question is more valuable than memorizing the formula itself. That kind of curiosity pushes beyond the surface.

In my work covering political corruption, I’ve seen this play out many times. The most revealing moments don’t come from knowing every fact right away. They come from knowing which questions to ask. When a public official offers a complicated explanation for something simple, I pause and think, “What would an honest answer sound like?”

That gap between what’s said and what makes sense is where the real story often begins.

From Row Four to the Front of the Conversation

Today, Morning Coffee Thoughts reaches thousands of readers who want deeper conversations about politics. I’m not the smartest person in the room, and I don’t pretend to be. What sets my work apart is the habit I picked up early on: asking the questions others overlook or hesitate to raise.

The irony isn’t lost on me. The kid who sat on row four, who struggled with philosophy, now spends his time questioning the philosophical foundations of power. The student who couldn’t keep up with textbook answers grew into someone who challenges the textbook answers politicians give the public.

The wooden box beside my seat didn’t define me. The questions did.

Your Critical Thinking Journey Starts Now

You don’t need a seminary education or a political blog to benefit from critical thinking. You just need to start asking better questions. The next time someone in a position of authority—whether a politician, a boss, or a news anchor—presents information, pause for a moment. Ask yourself which questions are worth raising.

When you find yourself in a disagreement, try shifting the goal. Instead of proving you’re right, ask what would help you understand the other side better, or what kind of evidence might change both your minds.

And when problems come up in your personal or professional life, don’t settle for surface explanations. Sketch a simple fishbone diagram. Put the problem at the head and list possible causes. Then ask why each one exists, layer by layer, until the questions run out.

Fr. Rudolf Horst probably never imagined that a breakfast conversation would shape how I approach politics decades later. His gift wasn’t a set of answers. It was a way of thinking that continues to push me to look deeper.

Critical thinking isn’t cynicism. It’s the courage to stay curious, to keep asking questions even when the answers get uncomfortable. Whether you’re sitting on row four or standing at the front, that journey begins with a single question: Why?

Contact us

subscribe to morning coffee thoughts today!

inquiry@morningcoffeethoughts.org

© 2024. All rights reserved.

If Morning Coffee Thoughts adds value to your day, you can support it with a monthly subscription.

You can also send your donation via Gcash: 0969 314 4839.