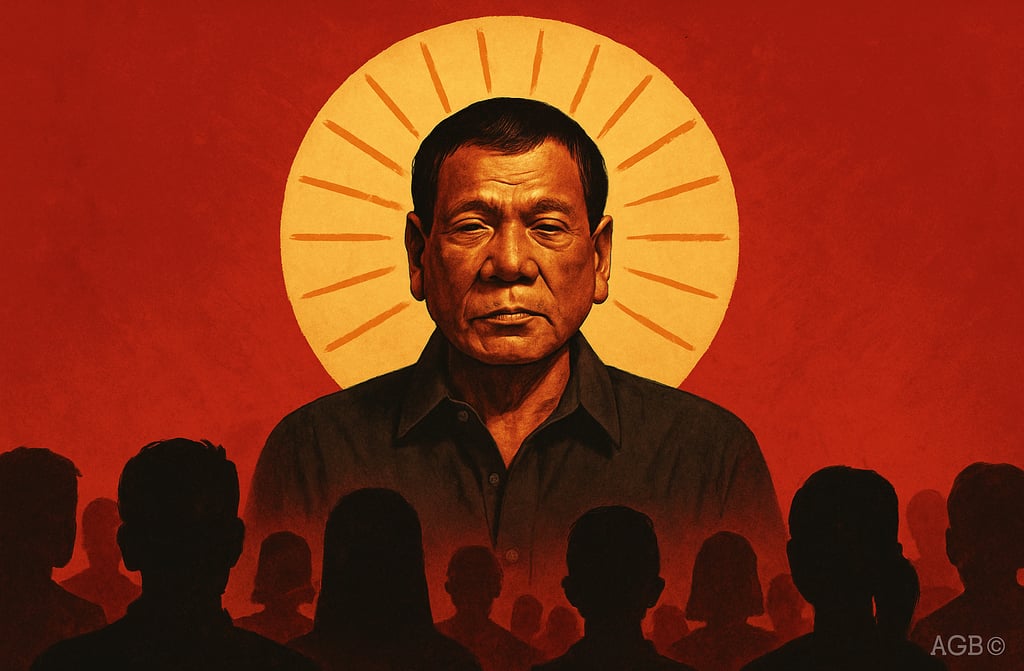

Why Religious Leaders and Members Support Duterte Despite Moral Contradictions

This blog explores why religious support for Duterte thrived despite moral contradictions, silence from church leaders, and public controversy. It reflects on how faith, politics, and survival often live in separate rooms in Filipino life.

It doesn’t make sense at first glance. A man who openly cursed the Pope, joked about killing, and mocked God—yet gained support from pastors, church elders, and Mass-goers alike.

But in the Philippines, it’s never just about what makes sense on paper.

This blog came from a topic request. Normally, I’d just respond to something like this with a Facebook post—short, direct, pang-scroll lang. But this one’s different. The question doesn’t just ask for facts. It quietly asks: what do you think? And that kind of question pulls something out of me. Maybe it’s the ex-seminarian in me who still wrestles with what faith means when it rubs against politics. I’m not an expert, and I won’t pretend to be. But I hope you don’t mind if I try to unpack it the best way I know how.

For some religious leaders, faith isn’t a line you don’t cross—it’s a bargaining chip. In the film Kingdom of Heaven, a bishop tells the knight Balian to “convert to Islam, repent later,” when faced with certain defeat. That scene wasn’t just about war. It was about how religion, in the hands of the fearful or the powerful, becomes transactional. Negotiable. And here in the Philippines, we've seen that too often—where convictions bend when survival, politics, or comfort is on the line.

The Messianic Political Framework

Duterte didn’t rise as a traditional politician. He was framed as a savior. Scholars call this a “messianic framework,” something deeply rooted in our political history (The News Lens, Inquirer).

This same motif ran through mass uprisings even before the 1896 revolution. In our history, there's always been a longing for someone to redeem the nation. Someone na parang itinakda ng tadhana. The past gets blurred, and all we remember is the strongman figure who said, “Ako bahala.” That kind of thinking hits hard in a country shaped by calamity and corruption.

So past sins and contradictions were forgiven, even forgotten, because what people saw wasn’t just a man—they saw a solution. Even if it came with blood on its hands (New Mandala).

Religious Pragmatism Over Doctrinal Purity

Most Catholic Filipinos aren’t rigid when it comes to politics. Faith and voting live in separate rooms.

Many believed Duterte could fix what others couldn’t—accountability, corruption, crime. That kind of pragmatism makes people overlook what’s written in doctrine (Pulitzer Center, UKDW Journal).

One religious scholar put it plainly: “Being Catholic is just one aspect of being a Filipino citizen” (UKDW Journal). Voting decisions were shaped less by theology and more by lived reality.

The Church, too, has been losing its grip on political influence. Maraming naiinis sa pakikialam ng simbahan sa eleksyon. Especially when some priests preach morality, then act otherwise.

So when Duterte came along, the support wasn’t blind—it was transactional. And for many, justified.

Reframing Drug Users as Sinners

Let’s not forget the war on drugs. The killings, the fear, the blood on the pavement.

And yet, some religious groups didn’t just tolerate it—they supported it.

How? By seeing drug users not as victims of poverty or mental health issues, but as sinners. Masama. Ligaw. A moral disease that needed to be cut out (Ateneo Research).

This theological lens gave moral cover to violence. “Thou shalt not kill” was reinterpreted as “Thou shalt punish sin.” For them, Duterte wasn’t defying God—he was doing His work (New Mandala).

The Appeal of Order and Stability

People of faith often crave stability. And when democratic institutions fail again and again, someone who promises order—even through violence—starts to look appealing (Pulitzer Center).

“Peace and order” became the new gospel. Due process was too slow. Reform wasn’t working. For many, Duterte's methods were harsh but necessary (Inquirer, Brookings).

To them, it wasn’t cruelty. It was disiplina. It was what they thought the country needed when nothing else worked.

Duterte’s Sophisticated Religious Relationships

You’d think a man who cussed at the Pope and challenged God would lose all religious backing. But no.

Duterte had strong ties with different religious groups. He knew how to speak their language, even if it was unorthodox. He worked with religious elites who believed he could restore peace in Mindanao or make environmental protection a real agenda (Pulitzer Center).

Even after those controversial statements, he insisted he had “deep and abiding faith in God.” His beef was with organized religion, not with the divine (PNA, Semantic Scholar).

Marami ang naka-relate. Disappointed with the Church, but still clinging to personal faith. For them, Duterte wasn’t irreligious—just real.

Religious Support in Names and Faces

This support wasn’t just theoretical. It had names, pulpits, and stages. Several prominent religious leaders and groups openly backed Duterte—some during his campaign, others throughout his presidency. Whether for influence, perceived alignment of values, or hopes for reform, their support gave Duterte something powerful: moral cover.

One of the loudest and most loyal supporters was Apollo Quiboloy, the self-proclaimed “appointed son of God” and founder of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ (KOJC). He wasn’t just a fan—he was a close personal and political ally throughout Duterte’s presidency (SCMP).

Then there was the G-12 network of Christian pastors, a massive charismatic movement with around 7,000 members. During the 2016 campaign, many of them threw their full support behind Duterte. Pastor Leo Carlo Panlilio of Destiny Church Manila even led prayers for him publicly, expressing hope that he would become a transformative leader (Inquirer).

Eddie Villanueva, leader of the Jesus is Lord (JIL) Movement—one of the largest evangelical groups in the country—also endorsed Duterte during the campaign. At the time, he believed Duterte would uphold “God’s agenda” and respect due process. Later on, though, Villanueva criticized the drug war’s violence and reminded his followers of the Sixth Commandment: thou shalt not kill (BenarNews).

Even the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) made a notable gesture. Senior LDS leaders, including Elder Quentin L. Cook and Elder Evan A. Schmutz, met with Duterte during his term. They gave him a Bible and a personalized image of Jesus Christ—an act that, while not a formal endorsement, signaled goodwill and alignment on shared values like peace, service, and family structure (PCO).

These figures helped shape public perception of Duterte—not just as a politician, but as someone worth listening to. Their voices echoed through pulpits and prayer rallies, lending moral credibility to a presidency surrounded by moral contradiction.

The Limits of Religious Opposition

Yes, the Church eventually pushed back. Hard.

Bishops condemned extrajudicial killings. Pastoral letters were read in Mass. But for many, it was too little, too late (Persecution.org, PhilArchive).

The Church’s moral authority had already eroded—scandals involving clergy had done damage long before Duterte stepped into the ring. He took full advantage of this, often saying the Church had “no moral ascendancy” to judge him (Philstar, Philstar).

Groups like the Jesus is Lord Movement did eventually speak out, calling the drug war “murderous” and invoking the Sixth Commandment. But by then, it was too late. Wala nang epekto.

Theological Compartmentalization

Here’s what many don’t understand: Filipinos can separate religion from politics without losing their faith.

It’s not dissonance. It’s diskarte.

Many saw no conflict between praying the rosary and voting for Duterte. Because in their minds, politics was about survival. And faith was about salvation (UKDW Journal, IJMRAP).

You’ll hear someone say “bahala na ang Diyos” after voting for a candidate they know is corrupt, or end a novena only to justify the killings in the next breath. These contradictions don’t always cause guilt. Sometimes, they’re not even seen as contradictions. They’re just how we live—divided but functional. Faith in one room, politics in another. Tahimik lang, tuloy ang dasal, tuloy ang boto.

The legal idea of separation of Church and State? For ordinary Filipinos, it simply meant: “My faith is mine, my vote is mine” (LinkedIn).

One thing I’ve noticed—despite all the Church statements and late-stage opposition—is that most religious figures who supported Duterte never really explained why. Hindi nila inamin, pero hindi rin nila itinanggi. Maybe it’s easier to stay quiet and let people assume your motives. Or maybe they believed it was obvious: order, discipline, peace—values they thought he could deliver. But part of me wonders if silence was also their shield, a way to support without being accountable.

Final Reflection

Religious support for Duterte wasn’t blind. It was layered. Complicated. Sometimes even reluctant.

To others, it looked like moral failure. But for many, it felt like choosing the lesser evil in a country where evil often feels like the only option.

We may not agree with it. But if we really want to understand why it happened, we need to stop judging from a distance—and start listening to what people were really dealing with.

Kasi minsan, faith isn’t just about believing in God. It’s about believing that something might still work—even if it doesn’t look holy.

And maybe that’s what hurts the most—not just that people turned to Duterte, but that many stopped looking to the Church in the first place.

Contact us

subscribe to morning coffee thoughts today!

inquiry@morningcoffeethoughts.org

© 2024. All rights reserved.

If Morning Coffee Thoughts adds value to your day, you can support it with a monthly subscription.

You can also send your donation via Gcash: 0969 314 4839.